KINGSWEAR HISTORIANS

Chairman: David Williams

Secretary: Michael Stevens

The First Kingswear Water Bills 1814

On 11th April, 1814, six leading Kingswear householders met to decide on charges to be introduced for the supply of water to villagers.

It being necessary that some regulations should be adopted for the preservation & repairs of the two Cisterns, and pipes belonging thereto, for conducting the supply of water to the Inhabitants of Kingswear, We the undersigned do agree to the following. First. That there be appointed two or more persons to Act as Conservators and that they shall collect three pence per head per annum for all and every person in the Village of Kingswear above two years of age except Publicans and that they shall pay six pence per head per annum for every person belonging to their family above two years of age, the one half to be collected immediately and the remainder in Six Months. Secondly. That the Conservators do purchase a Book into which shall be entered all the monies Received and Paid by them, which Book shall be produced Once in every Year (when all the Accompts are made up) for the inspection of the Inhabitants and that there be entered in this Book every person’s name that is liable to pay in consequence of their being benefited by the Water as also the number they are to pay for and likewise a list of all those who shall refuse or neglect to pay to the fund and it is further agreed that the names of all such as refuse or neglect to pay shall be fixed on the Door of the Conduit and also in any other place that may be thought proper and that they be excluded the benefit of the Water. Thirdly. That if any Person or Persons do Wilfully Injure the Pipes, Conduit or Cock that they shall be prosecuted for the same. And if any Person or Persons do turn the Cock purposely to waste the Water that they be fined one shilling each for every such offence. And any person giving Information shall receive one half the said fines on conviction. Mr Roope Harris Roope, Mr Daniel Farley & Mr John Poole having consented to Act as Conservators for the aforesaid Purpose, We do hereby agree to Appoint them for One Year, dated at Kingswear the Eleventh Day of April One Thousand Eight Hundred & fourteen as Witness our hands

James Thos Hugh Clements Chas Daniel R Smith Fawley H Roope

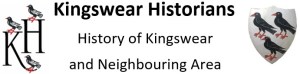

Below are short extracts showing receipts from all water users and payments for materials and tradesmen:-

Example Payments 1814

The Inhabitants of Kingswear liable to Pay for the Water at three pence & Public Houses Six pence per Annum to be collected half Yearly 14 June 1814

This ledger which Don Collinson holds runs from 1814 to 1840 and annually gives the names of all water users in the village and the number of residents in their houses including children. It is a wonderful source of information, beautifully handwritten, and gives insight into the community and the development of our civic services.

Kingswear Houses

Nethway House

by Mike Trevorrow

We were introduced to Nethway on 25 May by a short talk from the Historians giving a brief history of the finest house in our area.

Lynne Maurer was our very kind host, who provided a superb evening to about 55 members and friends.

Nethway is a ‘calendar house’: one chimney for each of the seasons, 52 windows for the 52 weeks of the year, 365 panes of glass (originally) and seven entrances/exits. It has a tunnel which is said to lead from underneath the front of the house to Boohay and Nethway Farms and then all the way down to Mansands. Within living memory this tunnel collapsed at Nethway Farm but previously it was used for heaven knows what purpose. We could supply some suggestions!

There is a resident ghost. A young girl who had been a servant, and who was seduced by one of the sons of the house, could not live with the shame and consequences of her resulting pregnancy and hurled herself to her death from the top of the roof. Both Lynne and her daughter have seen this girl; previous tenants record the same sightings. The house we see today is not the first house on the site; about the earlier house(s) we know nothing really, but certainly there was a Tudor house of some grandeur until it burnt down in 1696.

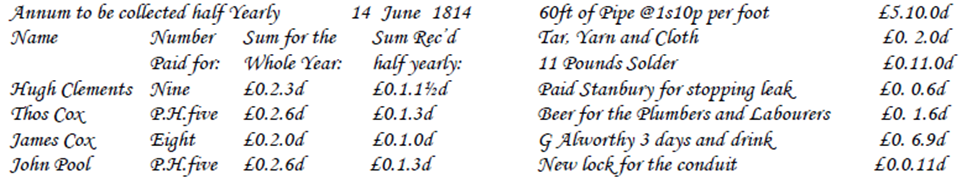

Nethway Front Entrance

The present house was built 1696 to 1699 by John Hody, who sold it before finishing to John Fownes who set in the front wall of the house a plaque commemorating the fact of his building. It is well-worn but still there today in its red sandstone. The earliest reference in print to Nethway is in 1192, and by 1380 there were seventeen different spellings of the name, including ‘Nethway-on-the-Hill’. The name means simply ‘by the way’, ‘near the way’ or ‘neath the way’, the way in question being the main road from Exeter to Dartmouth, which is about 700m away from the house.

From 1314 to 1435 Nethway was owned by the Cole family. There was a succession of John Coles but the earliest on record was a Devon Member of Parliament in 1417 and 1423. Two of the Coles became lords, two were mayors of Dartmouth, several went into the church and one daughter of a John Cole married the Lord Chief Justice of England in Richard II’s time. This august personage then became the first of the next family, the Hodys, to own Nethway. They became a very powerful family indeed, being resident from 1435 to 1699. During their tenancy it is written that Charles II stayed at the earlier Nethway on 23 July 1671 on his way from Dartmouth to Exeter. During the Hodys’ time, a font was dug up in the grounds and was said to be used for pig fodder but it is now the font in Kingswear church.

At our talk we had a descendant of the Hody family, a lady now called Gillian Huddie, who on the very evening of the talk told us her knowledge of her family. In 1747 Henry Fownes (17th generation!) married his cousin Margaret Luttrell of Dunster Castle taking the name Fownes-Luttrell. Their successive families lived in Nethway and Kittery but gradually moved to Dunster and their poor Kingswear houses fell into considerable disrepair.

The huge estate was sold by the Fownes-Luttrells in 1874, Llewellyn Llewellyn buying the Nethway portion. He set about improving the Nethway estate; it was no longer the 2000+ acre estate which John Fownes had accumulated, but was reduced to the house, its curtilage and Nethway and Boohay farms. Improvements were made to the farms as well as the house. During the Llewellyns’ residency in 1882 they lost a thirteen year old son who was drowned in the Dart and later suffered the death of twin girls at a couple of months old, and also their mother. The death of the son is commemorated in a window in Kingswear church.

It is notable that the school along the lane from Nethway was built by the Llewellyns; it is now the Dragon House. The Llewellyns stayed until selling in the late sixties to the McNeils, who ran some of the land as a market garden. They sold in 1978 to the Stewart-Bamms, who sold to the Corgatellis, who sold to the Smarts who made the swimming pool and tennis court, and they in turn sold to Lynne and her ex-husband in 1997.

The entrance hallway in Nethway House

Over the years the house has changed relatively little inside, at least as far as the main rooms are concerned; it maintains quite a grand staircase in the middle of the house and a most unusual ‘semi-newel’ lesser staircase at the back. The small stairs have a huge former ship’s mast as their central support running fully forty feet from top to bottom and is very unusual in a house of this high status. The doors and panelling in pine are of good quality, original, and worthy of mention. Also of good quality is the plaster-work in the outer hall and on the landing where swags, flowers and eagles ennoble the place. We think the big change occurred to the building as a whole in the early twentieth century, well before the house was ‘listed’ as being of architectural importance in 1971.

The ground at the front was raised a little, thus ‘swallowing’ some of the steps leading up to the front door; then there was a raising of the ground level at the side of the house facing the drive on approach. This meant that the bottom storey of four was completely buried, so that now the house appears to be only three storeys, the old bricked-up windows of the original kitchen, servants’ quarters, etc. are now in the cellar. At the back of the house a built-up walkway was added which gave the house a terrace, previously lacking. Round about 1978 the roof was re-formed; this was done by simply building a new single-pitch roof over the old twin-pitch one.

At some earlier time (we presume) the cornice at the top of the house was removed, thus making the house much plainer, not quite so typical of its day. It is, however, still a handsome house with two royal connections: Charles II (mentioned earlier) and Prince George, son of Edward VII, who planted a tree in the garden on 2 November 1878 when he was thirteen years old. He was a cadet at Britannia Royal Naval College.

Editor’s comment: Nethway, 1698, is a brick-built house.

Nearly 200 years passed before the first brick houses in Kingswear were built in the 1870s by Armeson with bricks from his Dartmouth brick works. These were Mount Agra (now The Mount), Agra Villas on Brixham Road, and the present Post Office and houses on the South side of The Square.

A Royal Coat of Arms for the Village Hall

The Steam Laundry was started in 1881 by railway engineer George Michelmore, initially in Dartmouth but two years later it was re-established in Kingswear in the vacant shipbuilding premises at the head of Waterhead Creek. Michelmore had obtained the contract from the Britannia Royal Naval College for all the laundry which was at that time being sent on a two week round trip to London. The Kingswear Laundry continued for the next 70 years until in 1950 the College transferred their business to Plymouth and the Laundry was forced to depend on local business. It ceased trading in 1970 and after an unsuccessful planning application for conversion to a motel, the buildings were demolished and houses built in what is now Waterhead Brake. The Michelmore family were proud of their initial ‘royal’ connection and collected over the years various carved wooden Coats of Arms which were installed on walls of the Laundry buildings. These included a Royal Coat of Arms which Don Collinson remembered seeing in the foyer of The Royal Dart Hotel and appears to have been acquired by a business partner of Mrs Sue Holman in the early 1970s when the Laundry was broken up. Mrs Holman kindly agreed that it should be given a wider viewing in the Village Hall and after professional restoration it was unveiled earlier this year on 27 April by Mrs Holman with Don Collinson and Barrie Tulloch, chairman of the hall committee.

A small plaque giving the history of the Laundry is affixed below the coat of arms.

My life in Kingswear during World War II.

by Tony Read

Tony Read and his wife live in Plympton but have close links with Kingswear.

Last year Mike Trevorrow persuaded Tony to set down his boyhood memories of wartime life in the village. These vividly bring alive the day to day happenings around him and some of the people he came to know. We thank him for letting us share them and are sure you will enjoy them.

My father was in the navy and we all lived in Plymouth. Every time he came home on leave it was usually to the remains of our house and a reduced family. Before he returned to his ship he had usually fixed us up with digs in some distant town, hoping that Hitler didn’t find out. We lived in Falmouth, Ilfracombe, Launceston, Penryn and a few other places the names of which escape me. The last place, and the happiest place, was Kingswear, and my big bruvver Pete and myself settled in till the war ended.

We were placed in one of a row of three-storey houses which, according to the rough map in front of me was at the end of Lower Contour (or could it be Higher Contour) Road. The far house was lived in by Frank and Granny Knapman who took us into their home and hearts, and it seemed as if we slept for the first time. Grandad Knapman was a porter on Kingswear station, Granny Knapman’s family lived next door and their daughter was called Myra (I think) who had three children. Monica was the eldest, then Lizzie and then Brian, who got up to all sorts of mischief and always had grazed knees and torn trousers. At the far end lived the Beerman family. Mr Beerman drove the small ferry boat. Their daughter was called Brenda. I only had one toy in the world, and it was a tattered wooden scooter that my Dad made for me out of odd bits of wood. It worked wonders for my image and increased my esteem and popularity; the equivalent to owning an E-Type Jag for pulling the dollies.

US landing craft loading at the Higher Ferry slipway

Behind these houses lived the Pollard family. They were all boys older than myself, and they were my heroes. They knew all the things that needed knowing: where the best trees to climb were, the nearest place to scrump apples, etc. They also did exciting things. Once they found a box of live 303 rifle ammunition. They drilled a hole through their gatepost that was a tight fit for the bullets and then put a six-inch nail against the end of the cartridge and hit it with a hammer. There was an almighty bang and the business end of the bullet whizzed and flew across the valley. They were always in trouble. They were my heroes, the Pollards.

My big bruvver, Pete, went to the grammar school over at Dartmouth and I went to the junior school just up from the station. We had a very elegant lady teacher once called Miss Matt-Souki and we bad-mannered little horrors used to drive her mad by pretending we couldn’t pronounce it and called her Miss Matooky. She hated us.

My father was sent to Ridley House after receiving injuries on his MTB (Motor Torpedo Boat). They used to sail from Falmouth and go across the channel to sort out the German ships, and then tear back home like scalded cats, and go straight down the pub.

The steep gardens of the cottages led down to a road which we called Lower Road; its real name was Brixham Rd. We all used to scamper down there to a bungalow and ask Mrs Bunn if John could come out to play. We thought they must be pretty rich because it was rumoured that they had a car. Nobody had a car then. One of my greatest delights was to have a ride on The Mew – that beautiful Great Western Railway steamer that was kept in permanent steam with the sole purpose of completing the last two hundred yards of the trip to Dartmouth for anyone who bought a rail ticket to that town. It must have cost a fortune to run, but for me it was paradise. I soon grovelled my way into the skipper’s good books and was allowed below decks in the engine room to watch the magnificent triple-expansion, reciprocating steam engine come to life and almost silently push the ship gently across the river. In that engine room it was the first time that a little boy had shed tears of happiness for quite some time. But me being a nasty little horror I showed my gratitude by carving my name on the taffrail at the stern of the ship. Years later, when I heard that The Mew was in Demelweeks scrapyard waiting to be broken up, I headed there and pointed to my name and thus my shameful vandalism, bunged the man a tenner, and said, ’Save me that piece’. He nodded and pocketed the tenner. I think you know the end of the story…… serves me right.

In the summer time we all used to go down to Lighthouse Beach (for beach read rocks) and although the water was almost always at minus 95⁰ Centigrade we loved it. The very active sewage outfall pipe didn’t seem to worry us (there was no `elf and Safety’ then) but we most likely picked up a hatful of immunities that saved our lives many times since.

If we were off for the whole day it could mean a trip round to Millbay Beach and that had real sand. Cor heck! More than once I saw aeroplanes flying down over the river, these were usually Spitfires identified by the heavenly sound of their Rolls Royce Merlin V12 engines. They might well have been chasing enemy planes, but I never saw any. That didn’t stop me from telling my spellbound mates back home that the whole Battle of Britain was fought here – ‘and I saw it all happen, so there’!

Evacuee girls in The Square Kingswear, VE celebration

Eventually our house had a new roof, walls, windows and doors and it was time to go home. For me being in Kingswear was a magical time and I lived among some wonderful people.

My big bruvver, Pete, joined the RAF and died with his crew, flying a Wellington bomber in 1951.

I joined the Merchant Navy and terrified the passengers on Union Castle liners before they threw me out.

I often think of the Kingswear people and wonder how many are still around. They will always be alive in my memories.

Tony Read,

Plympton.

September 2008

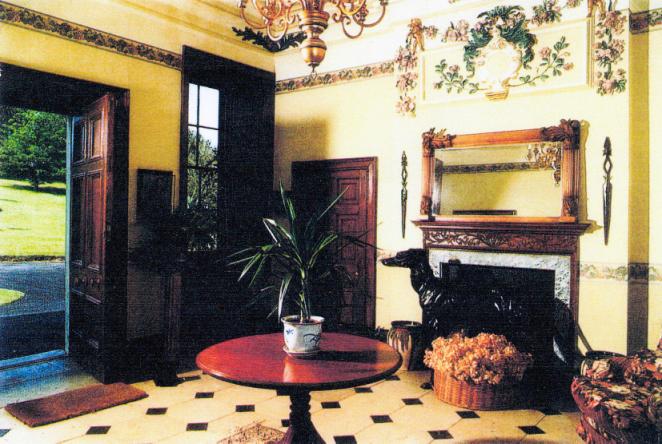

The Radar Station at Coleton

Reg Little’s ambition of achieving recognition of RAF Kingswear is coming to fruition in an unveiling ceremony in November.

The National Trust car park at Coleton Camp was the site of this important radar station during WW2. Because of the fear of an invasion it provided the eyes and ears for early detection of this and any threat of enemy action. The attached information board will encourage folks to enjoy the current delights of our coastline as well as indicating how a radar site functioned.

Much more detail about the site can be accessed via the National Trust website.

The Escape of the Ragamuffin f

from Reg Little

This story of the Ragamuffin was sent in a letter to Reg Little by the Jersey Museum who have also supplied the photograph of the boat and confirmed that it is still on display in the Jersey War Tunnels.

In 1940 Denis Vibert, a Jersey man, was 22 and during the German occupation planned to escape from his home on Jersey. He had returned there in 1937 after training for the Merchant Navy and service with the Blue Funnel Line.

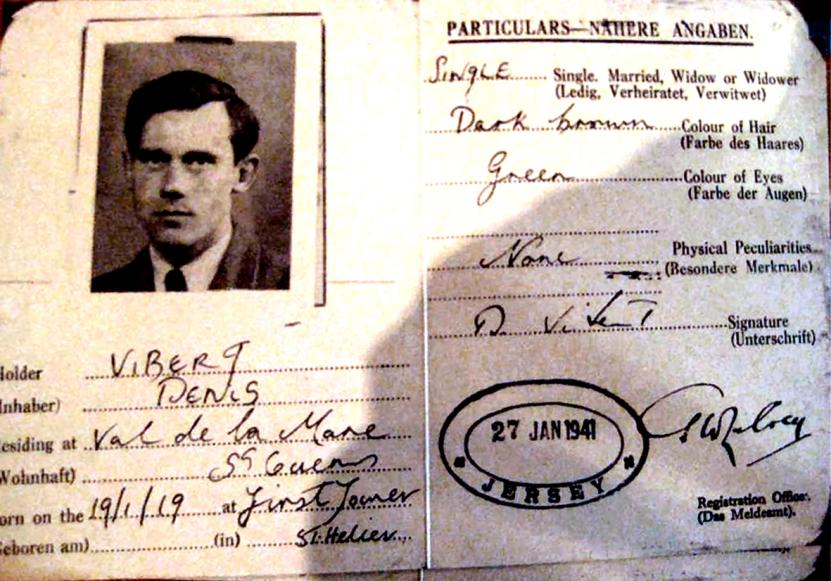

German occupation ID registration paper

In November 1940 he made his first attempt to escape. It was to be by rowing to England, and in view of the necessity of being out of sight of Jersey and Guernsey in daylight, he planned to row from Jersey to certain rocks south of Guernsey on the first night, with the intention of hiding there during the following day. This first part of the adventure was successful, but unfortunately the wind changed the next day and it was impossible to continue the journey the following night. He waited four days but the conditions did not change. During this time he developed influenza, and finally he decided to abandon the attempt and return to Jersey. The return was not uneventful as his boat was wrecked and he had to swim a quarter of a mile to shore. His absence had not been discovered by the Germans.

He spent the summer of 1941 preparing his 8ft rowing boat Ragamuffin. He added a couple of planks after steaming them using a kettle, to raise the freeboard. He also painted the boat grey to make it more difficult to be spotted from the air.

On the evening of Tuesday 21 September, he launched Ragamuffin from Bel Royal in St Aubin’s Bay before the Germans had completed building the anti-tank walls. He rowed the first four miles before using a small outboard motor and the ebb tide to head west. By dawn on the 22nd he was 15 miles west of Guernsey and changed course for Start Point. While trying to refuel his engine in a choppy sea, his fuel tank was contaminated by salt water and the engine rendered useless so it was a case of rowing northward. In the late afternoon of Thursday 23rd he feared that the tide had taken him too far west and so he altered his course more easterly. On Friday afternoon he spotted Portland Bill and as evening fell he was able to use his small sail for the first time in the hope of making Weymouth by Saturday 25th. Happily during the last dog watch on Friday 24 September, he was spotted by leading seaman F Troughton on board the Hunter class destroyer HMS Brocklesby and was picked up. It was calculated that he had covered a distance of 150 miles.

HMS Brocklesby continued her patrol and Denis and his boat were landed at Dartmouth where he was met by army police and naval intelligence and taken to Plymouth while Ragamuffin was taken to the Naval College.

Some time after his debriefing he went to pick up his boat and was charged ten shillings duty by Customs for having imported a boat worth £5 into England! The boat was then taken to Aldermarston before being brought back to Jersey. For a long time it was on show in the grounds of La Hougue Bie museum

For the rest of the war Denis served in the RAF in a Wellington bomber as part of the Atlantic Coastal Command. After the war, married to Ruth, he studied design in Quebec and then moved to Maine USA where he opened a successful pottery studio/workshop. He died there in 2004, aged 85.

A memorial service was held in Jersey. His tiny boat Ragamuffin was brought to the service and placed beside the pulpit with flowers from his wife being the only adornment. Ragamuffin was then loaned to the Jersey War Tunnels where it is on permanent display inside the reception building.