KINGSWEAR HISTORIANS

Chairman: David Williams

Secretary: Michael Stevens

Where was Trinity Chapel?

Michael Stevens

The church of St Thomas of Canterbury in Kingswear was rebuilt in 1845 although the tower is from the original building and dates from about 1173. The font in the church is very weathered as if it had been kept outdoors for a considerable time and it was suggested to me that perhaps the font came from the old Trinity Chapel. Where was Trinity Chapel?

Its name only appears twice in old documents, on Saxton’s map of 1575 and Bowen’s map of 1754. The latter seems to be a copy of the former and reproduced here as it is a little clearer. Kingswear is not mentioned in the 1086 Domesday Book but nearby Coleton is listed, which suggests that the latter was more significant at that time. Coleton is on high ground about two miles east of Kingswear. In those days settlements near the coast were vulnerable to raids from the sea and so the seat of the lord of the manor was often a distance inland where he would also build his chapel.

A chapel at Coleton is mentioned in the Totnes Priory deeds in 1258, when Nicholaus, then Prior of Totton, granted to Martinus de Cholatun a chantry in his chapel of Cholatun and one of the twenty days when a service was to be celebrated was the feast of Holy Trinity. The dedication of the chapel was not stated and the inclusion of Holy Trinity does not prove that Trinity was its name although the omission of a reference to the day would have cast doubt that this was Trinity Chapel. Clearly there was a chapel in existence at Coleton in 1258 and perhaps much earlier. Although some roads are shown on the old maps they seem mainly as an aid to navigation by sea. The depiction of Trinity Chapel on the maps seems most likely to be there for that purpose.

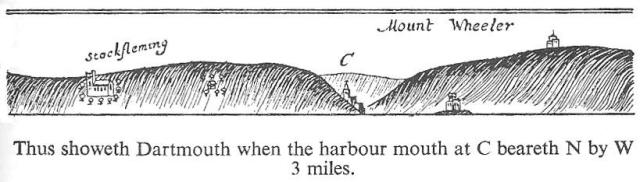

This sketch appears on Captain Collin’s Coastal Pilot of 1693 and shows a tower on top of a hill together with the two castles, Dartmouth and Kingswear, either side of the entrance to the river. The old farmhouse at Coleton was severely damaged by a fallen tree in 1938 and now largely demolished.

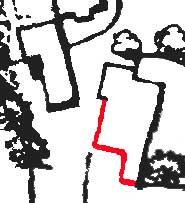

The original building is shown on the tithe map of 1838 and in better detail on the Ordnance Survey map of 1864. The building in the top left is the existing south wing of the old farm house and now used as a barn. The land mark on the top of the hill in the 1693 Coastal Pilot appears to be a tower with a short spire or mast on top and two rooms in front.

It is to be assumed that this is a reasonable sketch of the actual building since navigators had to be able to clearly identify it from other buildings which might also be in view. It is quite credible that the two southern faces of the building are those of the southern walls of the building on the map. The northern corner of the building on the map shows a slight widening and could well be the square base of a tower. Part of the walls of this building still exist and are shown in red. In two places there are doorways through the walls. While this seems to match the building in the Coastal Pilot very well one negative aspect of this being Trinity Chapel is that the rooms, at least as depicted in the tithe and OS maps, do not align in an east-west direction which is customary for a church or chapel. However not all chapels of the time had this orientation particularly if they had been converted from a previously existing room, which was common in those times. So perhaps it is the chapel.

It is unlikely that the font in Kingswear’s church is from Trinity Chapel as I have found another one with a better claim. The photograph opposite is of a font dating from the Norman period which was found at Coleton Farm.

Michael Stevens

This is a précis from an article on the Historians page on the Kingswear website http://www.kingswear-devon.co.uk

Are you enjoying this newsletter? Kingswear Historians’ aim is to promote our local history in many ways. We would love some more help from volunteers or even some new committee members! D

Do you live in an old house? Would you consider writing your ‘House History’ for a future newsletter? We will help if you wish!

Please contact David Williams or any of the Committee members.

Kingswear Ferries

Mike Trevorrow

We‘ve got three now, one’s moved, one’s new, but we have actually had a ferry across The Dart since early on in the fourteenth century (first mentioned in 1365 and probably much earlier than that, but unremarked or recorded).

Now Dartmouth is by far the bigger of the two communities of Kingswear and Dartmouth but in the thirteen hundreds this was not particularly so. It is likely that the politics of the landowners were more favourable to development over in Dartmouth, although the Kingswear side had much to offer in terms of roads to Exeter, Brixham, etc..

The Lower Ferry seems to have been the earliest and for much of its life it was a ferry boat rowed from Kingswear slip (as now) over to the present southerly slip in Dartmouth, or at least nearby on the other side of the ‘Island House’. Another, larger horse ferry existed, leaving for most of its life from the slip at Hoodown, just north of Waterhead Creek. During the 18thC and 19thC this was powered by two men with ‘sweeps’ and was capable of carrying a cart and two horses. The site at Hoodown was better for vehicular access to the platform; it was also the site of some sort of ferry from very early times indeed. In a busy river, mishaps are bound to occur and they have on a number of occasions, one of note was the collision of an old platform ferry with the ex-naval sloop Enchantress on Whit Monday in 1935.

Change came in 1857 when The Dartmouth and Torbay Railway was authorised to set-up a steam ferry to carry its passengers from Kingswear (Kingswear Station was opened in 1864) to the landing at Dartmouth which was a pontoon close to where the Station Restaurant is now sited. The ownership of the railway changed several times and the steam boats used by the companies also changed. Perseverance was the first, and she proved unsuccessful, was briefly replaced by Louisa and New-comin. Dolphin came next as the proper replacement for Perseverance and she proved good at her job because she was used by the various companies for the next forty years.

The Mew was possibly the most popular and long-serving of the steamers, she managed 48 years’ service, including several re-fits to cope with the development of motor vehicles, extra comfort demanded by passengers, and the ravages of time. She went to the service of the Dunkirk evacuation in WW2 but was rejected for her unsuitability for landing on beaches. She was brought out of service in 1954 to great acclamations and celebrations.

The ‘Passenger Ferry’ as we have come to know it, has always had the responsibility of carrying general passengers, apart from the rail passengers, ever since its inception in 1857.

The Higher Ferry or ‘Floating Bridge’ as it is called by some was another 19thC candidate. 1828 saw the first design for a floating bridge after the suspension bridge of earlier that same year had been rejected. James Meadows Rendel’s design was taken-up and built in 1829 with a two boiler four horse-power engine at its centre. Propulsion was by means of two cast iron chains attached to large granite blocks on either shore. It was not a financial success however and was replaced in 1836 by a two-horse-drawn vehicle with the horses in a treadmill. They were said to be ‘blind’, but this may not have been literal, their vision could have been much restricted, we do not really know.

After a disastrous storm in 1855 the float was sunk and then deemed unworthy of salvage so a new one was built in 1856 and this used horses until 1867. This is where Philip and Son enter the fray by building the first of a series of their ferries, this time steam, which ferried the service until the last one was taken out of service in 2009.

Interestingly the 1867 steam ferry could cross the river in the same time as the 2009 one, three minutes.

The Free French Medal

David Williams

Soon after France fell to the invading German forces in the early days of World War 2, the Dart witnessed a Free French naval presence which lasted for much of the conflict. Initially the two tugs L’Isere and L’Aube arrived and then continued to operate in the estuary throughout the war. Several Motor Boat Flotillas were developed early in the war with the intention of providing coastal escort and defensive patrols as well as air sea rescue. Forces Navales Francaises Libres (FNFL) manned a number of these boats and by early 1943 the 23rd MTB Flotilla was formed. This unit was based in Kingswear with eight new Motor Torpedo Boats, French crews and three British Liaison officers. The MTBs would be seen moored alongside Belfort, a French supply ship, at the jetty now used by the Dart Harbour & Navigation Authority adjacent to Hoodown.

The Forces Navales Francaises Libres had their HQ in Brookhill and the Officers were billeted in Longford House, while crews were based in Brookhill, Kingswear Court and other local houses. The Royal Dart Hotel became HQ of the Royal Navy coastal forces which had overall control of the 23rd flotilla. The first of these new boats were 72 foot Vosper MTBs weighing in at 60 tons and powered by three 1200hp Packard engines offering up to 40 knots and a range of 420 miles. Their fuel was 2500 gallons of petrol!

They carried two 21” torpedoes, a variety of machine guns, hand grenades and depth charges. The crew was made up of Captain, Midshipman, Coxswain, Signalman, Torpedo man, two gunners, two radar operators, two radio operators and three mechanics.

The Flotilla was involved in a large number of incidents mainly across the channel towards the Brittany coast and the Channel Islands. On the night of 8 May 1943 four of the flotilla were patrolling in pairs near the coast of Jersey. They spotted a convoy of two cargo vessels with an eight boat escort. Two MTBs attacked from one side to create a diversion while the other two MTBs fired their torpedoes from the other side. The larger cargo vessel sank quickly. The rest of the convoy was now heading for St Peter Port in Guernsey. A further skirmish resulted in another escort boat being shot up before reaching the harbour. One of the MTBs suffered damage but was able to limp home, the other three returned safely as well. General de Gaulle conferred on these boats the Ordre de L’Armee, a bravery decoration awarded to a ship.

In total the 23rd Flotilla carried out more than 450 patrols sinking 5 German ships and damaging more. The MTB crews were decorated many times including 1 DSO, 5 DSC, 2 DSM, multiple French medals including 85 Croix de Guerre.

To mark their gratitude to the people of the village, a silver medal was awarded to Kingswear in 1967 by order of the Inspector General of the French Armed Forces ‘in permanent acknowledgement of the hospitality extended to the Free French Forces’. Their letter to the Parish Council stated that ‘the parish was virtually regarded as the HQ of the Free French Navy’ These medals disappeared from Kingswear but were returned to the village during 2009. The Parish Council plans to display them in an appropriate medal case in The Sarah Roope Trust Rooms in the near future.

Thanks to Tony Higgins for his permission to use information from his book ‘The Free French in Kingswear’ – Dartmouth History Group and Michael Stevens for his photograph of the medal.

A Cannon for Kingswear

David Evans

When Neville Oldham was with us in the Village Hall for his fascinating talk “Pirate Gold”, he also told us during the after coffee discussion of his finding many years previously a group of nine iron cannons lying on the sea bed a short distance off shore from Kingswear Castle. At that time he took no action concerning them apart from recording the find. However, six years ago an enthusiastic local young diver, now no longer in the area, persuaded him to raise one of them and begin the lengthy desalination process to conserve it, initially in Dartmouth but subsequently at the farm of a friend at Cornworthy.

The cannon weighs 1.5 tons, s 7’4’’ in length and has an 8” muzzle.

It was only while turning over the cannon during the move to Cornworthy that the date 1577 was found to be etched on the barrel. It cannot be certain that this is original but with the elegant style it points to it being an Elizabethan cannon. The other eight guns in the cluster, although covered with concretions, appear to be of similar size and shape and how they came to be on the sea bed remains a puzzle still to be solved. It was thought initially that they may have been taken from nearby Kingswear Castle but their size and weight would seem to make this unlikely. It seems more probable that they are the result of a shipwreck or stranding on the rocky sea bed although no records or evidence of one have been found so far.

Neville hopes to arrange to carry out a thorough archaeological survey of the sea bed and to continue searching local archives for evidence. With conservation nearly complete, he was anxious to find a good home for his “baby” and completed ownership formalities by registering it with the Receiver of Wrecks. His generous offer to donate it to Kingswear was accepted by the Parish Council on behalf of the Village with the Historians arranging for carrying forward the project. The Darthaven Marina kindly agreed that a wooden carriage for the cannon would be built by an apprentice on their staff and this is now in progress. When fully completed, the cannon will be displayed in a prominent position facing out across to Dartmouth with an information board concerning its history and recording all those who have helped in bringing it to Kingswear.