Summary.

Trinity Chapel was located at Coleton Farm in the parish of Kingswear since before 1258. Coleton was the seat of the local lord of the manor and, unlike Kingswear, is listed in the Domesday Book. For many years the chapel tower was used as a navigation aid to locate the entrance to Dartmouth harbour and when it fell down it was replaced by the present Day Mark.

The first recorded church or chapel in the Kingswear area is St Thomas of Canterbury which is mentioned in Totnes Priory deeds1 dating from the period 1170 to 1196.

I, Willelmus de Vasci, for the safety of my soul and of my ancestors and of the soul of Willelmus Buzun my lord, have conceded and confirmed to God and to the Church of the Blessed Mary of Totonia and to the monks serving God there, half of the whole of my land which I have in Kingeswere, just as it can be reasonably divided by just men of our mutual friends, that is to say for the increase of the maintenance of the chaplain who for the time being serves the chapel founded in honour of the Blessed Thomas the Martyr at the said Kingeswere.

Thomas Becket was murdered in 1170 and canonised in 1173 so it is assumed that the church dates from just after 1173. The church was rebuilt in 1847 except for the tower which was retained.

Yvo de Vasci had been one of William the Conqueror’s army and was given the barony of Alnwick in Northumberland in 1093 when the previous incumbent, Gilbert Tyson, rebelled against the king. Kingswear would have provided a link with the family’s still extensive holding in Normandy.

Kingswear is not mentioned in the 1086 Domesday Book but nearby Coleton is listed which suggests that the latter was more significant at that time. The Domesday Book records that Coleton was held by Warinus* under Judhel of Totnes2. Judhel was the person who built Totnes priory in 1088. Coleton is about 2 miles east of Kingswear and has an elevated position. In those days settlements near the coast were liable to raids from the sea and so the seat of the lord of the manor was often a distance inland where he would also build his chapel. (Similarly on the Dartmouth side of the river Townstal (Dunestal in Domesday) is at the top of the hill and the church there predates by many years the chapel of ease of St Clare and the church of St Saviour in the town of Dartmouth.)

Arthur Ellis2 reported that in the time of Henry II (1133 to 1189) Coleton was held by Martin de Fishacre. The deed quoted above was witnessed by Osmundus de Coleton and a second deed, by Willelmus’s son Walterus confirming the gift, was witnessed by both Osmundus de Coleton and Martinus de Fissacre. A person named Martin de Fisacre is recorded as living at Coleton in 1243 and a Martin de Choletun in 12583. Presumably these Martins are the same person.

Ellis also writes that the lords of the manor were encouraged to build their own chapels by a law exempting from taxation payable to King or Pope any 20 acres of land on which a church or chapel was built.

A chapel at Coleton is mentioned in the Totnes Priory deeds in 12584, when Nicholaus, then prior of Totton, granted to:

Martinus de Cholatun a chantry5 in his chapel of Cholatun on the condition that the foresaid Prior shall cause the chaplain of Brixham to celebrate divine service in the chapel on twenty days of the year, namely the first four days on Christmas, the day of the Circumcision, the day of the Epiphany, the day of Purification, the first day of Lent, the day of the Annunciation of St Mary, the first three days of Easter, the day of Ascension, the day of Pentecost, the day of the Holy Trinity, the day of St John the Baptist, the day of Saints Peter and Paul, the day of the assumption of St Mary, the day of All Saints and the day of Souls.

- This is probably Warin de Vasci, son of Yvo de Vasci.

The above does not give the dedication of the chapel and the inclusion of the feast of the Holy Trinity as one of 20 days when a service was to be held in the chapel does not prove that Trinity was its name although the omission of a reference to the day would have cast serious doubt that this was Trinity Chapel. Clearly there was a chapel in existence at Coleton in 1258 and could have been built much earlier, possibly even before that in Kingswear.

G H Cook6 writes that

“The significance of the chantry in the religious life of the later Middle Ages can hardly be over-emphasized. The doctrine of Purgatory was no „fond thing vainly invented,‟ as it is termed in the Book of Common Prayer, nor less readily accepted was the teaching that souls in that intermediate state could be benefited by intercessory prayers and the recitation of masses.” “The considerable properties with which many Chantries were endowed and the costly chapels that were built for the recitation of masses afford evidence of the very real doctrinal belief underlying their foundation.”

He also reports that almost without exception the chantry chapels that still remain are in the larger churches and cathedrals. According to Cook (p 17) the earliest recorded Chantries are at Lincoln Cathedral (1235), Lichfield (1238) and Ely (1254).

“No doubt other Chantries were unrecorded at the time but very few date earlier than the fourteenth century.”

If this statement is true then the granting of a chantry at Coleton in 1258 must have been exceptional.

Coleton Fishacre Farm is now known as Coleton Barton Farm and is not to be confused with Coleton Fishacre house and garden which was built by Rupert D’Oyly Carte in 1923-6.

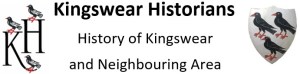

Figure 1 1838 tithe map of the area

The National Trust Archaeological Survey7 lists three possible sites for chapels in the area:

- “Coleston” Chapel (NT ref. 100,457), said to be a fourteenth century chapel at the hamlet of Coleton and pulled down in about 1873. (The location is shown by a blue spot in figure 1 which is taken from the tithe map of 1838)

- Coleton Fishacre Chapel (NT ref. 100,458) stated as a medieval chapel recorded at Coleton and thought to have been built by the de Fishacre family. (purple spot) .

- Trinity Chapel (NT ref. 100,459) at Downend. The National Trust description states that the site is shown as an admiralty flag station on the 1800 Ordinance survey map and was used as radar station during the 1939-45 war. (red spot)

Shirley Blaylock, National Trust regional archaeologist, has suggested that it is most likely that there was only one medieval chapel at Coleton, probably dedicated to the Trinity, and that it was lost before accurate mapping existed. This could have led to confusion as to where it was located and also led to the supposition that there was more than one chapel. The chapel could be have been anywhere within the hamlet of Coleton and the surrounding fields.

The fields marked in green in figure 1 are listed on the tithe map of 1838 as Higher Church Park, Middle Church Park and Meadow (left to right). They are feoffees (held in trust) to St Mary’s Church in Brixham and do not appear to be associated with the chapel at Coleton. The two fields near to Coleton, shown pink, are named as Lower Chapel Park and Upper Chapel Park. It was the custom to endow chapels with land and that is presumably what these two fields are. Following the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII in 1524 and the Chantry Act of 1547 this land and any associated chapel would have been sold into private hands. The chapel fields were included in the Fownes-Luttrell sale of Coleton Farm in 1874 while the church fields were listed as Church Land on the sale map and not available for purchase from him.

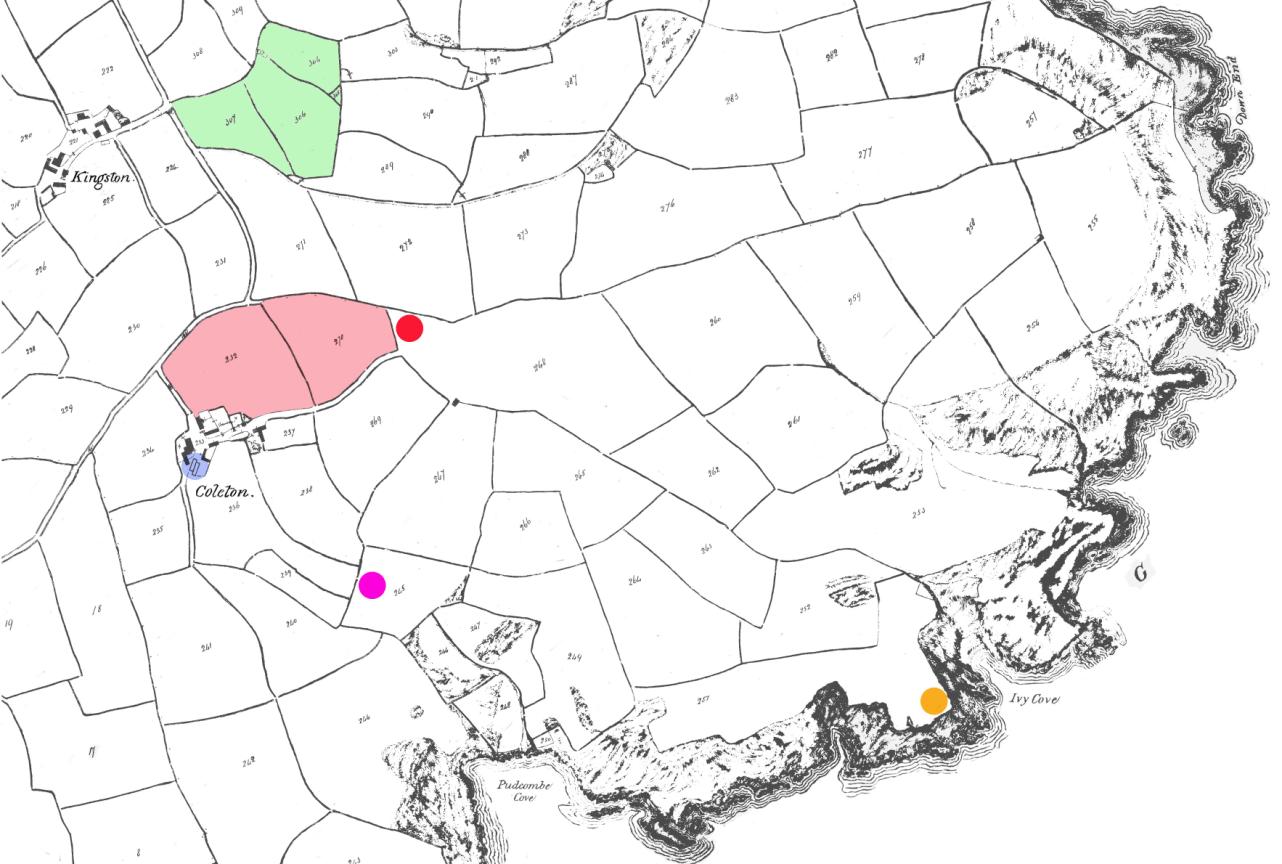

There is a fourth possible site, marked orange in figure 1. Mr Eddie Shepperd was head gardener of the modern Coleton Fishacre house and garden (built in 1923-6 by Rupert D’Oyly Carte) when it was subsequently owned by Rowland Smith. He became a warden with the National Trust when that institution bought the property in 1982 and has intimate knowledge of the local area. Mr Shepperd’s reasoning follows from two early maps, Saxton’s map of 1575 and Emanuel Bowen’s map of 1754, see figures 2 and 3. These maps show Trinity Chapel to be on the coast and if this is an accurate positioning then the site near Ivy Cove is a good candidate. These two maps are the only historical references which give a name to the chapel. However a site right on the coast does not accord with any of the three possible sites suggested by the National Trust.

Figure 2 Saxton’s map of 1575 Figure 3 Bowen’s map of 1754.

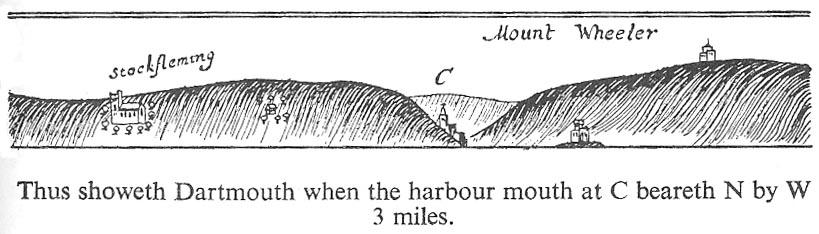

Captain Collin’s Coastal Pilot of 1693, Figure 4, shows a tower and buildings at the top of the hill approximately where Coleton Farm is. This tower obviously assists ships to find the entrance to Dartmouth Harbour which from other angles is hidden in the folds of the cliffs. The two buildings shown close to the water’s edge are Dartmouth and Kingswear Castles which guard the entrance to the river Dart.

Figure 4 from Captain S Collin’s Coastal Pilot of 1693

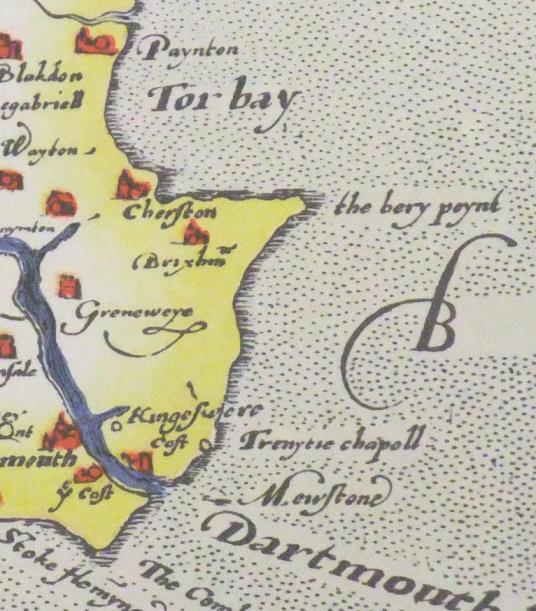

Figure 5 Map of 1538

A coastal map was drawn in 1538 in the time of Henry VIII – shown in Figure 5. The map is mainly concerned with coastal protection and shows several proposed castles around the coast which are labelled “not made”.

The castle on the east side of the river is Kingswear Castle which still exists. A ruined tower is shown south of the castle. However the map in not a very accurate representation of the local geography and the tower could be the same tower as in the other maps which place the tower to the east of Kingswear. The fact that the tower is shown at all on these three maps indicates that the tower was of maritime importance as few roads, if any, are shown.

The Ordnance Survey produced a map in 1864 although this was not published until 1880. This map, part of which is in figure 6, shows the buildings at Coleton perhaps a little more accurately than the tithe map of 1838. The probable site of the chapel is marked in blue.

The land mark on the top of the hill in figure 4 appears to be a tower with a short spire or mast on top and two rooms in front. It is to be assumed that this is a reasonable sketch of the actual building since navigators had to be able to clearly identify it from other building which might also be in view. It is quite credible that the two southern faces of the building are those of the southern walls of the building in figure 6. The northern corner of the building in Figure 6 shows a slight widening and could well be the base of the tower in figure 4.

Figure 6 1864 OS map of Coleton Farm showing the site of the chapel in blue

Nethway

A deed8 of 1192 reports the leasing of land at Nethway to Martin de Fishacre and over the years the importance of Coleton seems to have waned in favour of Nethway Manor. Following the Chantry Act of 1547 the land and the chapel building at Coleton would also have been sold which might have seen the end of the chapel as a place of worship whereas Nethway could have needed its own chapel. From about 1300 onwards contemporary records seem to refer mostly to the residents and owners of Nethway with little further mention of Coleton. Nethway is about two-thirds of a mile due north of Coleton Farm. Arthur Ellis devotes 12 pages to the history of Nethway Manor but only two to that of Coleton Farm.

The Cole family were owners of Nethway from 1314 when in 1435 it passed by marriage to Sir John Hody, then Lord Chief Justice of England. It remained in the Hody family, almost continuously, until sold to John Fownes in 1696.

Polwhele9 states that there was a chapel at Nethway which was “suffered to fall to ruin by Mr Huddy, who used the font from the chapel as a pig’s trough.”10 Mrs Gillian Huddy, a descendent, recalls a family story of the unearthing of a font in a field near Nethway11.

Kingswear’s font

Kingswear’s church of St Thomas of Canterbury contains a font, figure 7, which is very weathered as if it had been kept outdoors for a considerable time. Beatrix Cresswell12 reported that “The font is octagonal, of Purbeck marble, having shields on the panels. It is much battered, and has suffered badly from weathering, having been used for many years as an ornamental garden vase”. Another version13 holds that it was found in a pig sty at Boohay (which is less than a quarter of a mile east of Nethway House). This belief also maintains that the font was originally in Trinity Chapel. Possibly the font was moved to the chapel at Nethway following the possible closing of Trinity Chapel at Coleton.

The top section is separate from the base, is slightly less weathered and contains a flat bottomed vertical sided lead bowl. One face is not sculptured and its flat surface still shows signs of the fine finish which is possible with Purbeck marble and which made it so popular as a material for church stonework. On only one face is there a reasonably clear image which appears to be two chevrons with possibly a lion passant above, figure 8. This side is one position to the left of the front of the font, assuming that the un-sculptured face is the back. So this coat of arms may not be that of the donor of the font but of an overlord or local religious leader. Figure 8 Coat of arms on the font

Figure 8 Coat of arms on the font

From the close of the fourteenth century onwards there was a prevalence of heraldic decoration on the perpendicular sides of the bowl. Tyrrell-Green14 maintains that “Churches were at this time more closely connected with the personal element in religion, and the multiplicity of chantry chapels which played so prominent a part in the church life”. “The shields that so frequently form the centres of quatrefoiled panels are in many cases blank, but the occurrence of such shields gave a first-rate opportunity for the blazonry of heraldic charges. Personal coats-of-arms are often thus figured upon fonts, sometimes in conjunction with the arms of religious houses or other coat of special significance in a particular district”. This seems to describe the font in the church at Kingswear exactly.

Figure 9 Font from Coleton Farm

According to Tyrrell-Green many of the Norman fonts were made of material imported from Tournai in Belgium. However Bond15 states that from the thirteenth century marble fonts also came from Purbeck in Dorset – as Beatrix Cresswell claimed for the Kingswear font, see 6 above. He writes that these fonts usually had octagonal or square bowls and “were immensely popular, they are found scattered about the country in very great numbers, especially where they could be waterborne”. Mr Shepperd also has a font which he retrieved from Coleton Farm where it had been used as a water container in a pig sty. It is now located in his front garden which is part of the National Trust estate. It is shown in figure 9. About a third of the font is below ground.

According Tyrrell-Green to stone fonts mainly date from the Norman Conquest and the early ones had a cylindrical or tub-like shape, perhaps like figure 9, and he quotes several examples of such fonts in Devon. He goes on to state that “The octagonal bowl then became the normal font bowl in this country during the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries” – as in figure 7.

Also of possible relevance is the comment “The period of disorder inaugurated by the Reformation culminated in the Puritan regime of the Commonwealth, and during this period many ancient fonts perished, being either wantonly destroyed or, in many cases, degraded to base uses and removed from the old parish churches that they might serve for flower-vases in gardens, pig-troughs in farmyards, or other secular purposes”. Tyrrell-Green quotes a number of examples where a font has been discarded from one church only to be then used in another when that was restored or rebuilt. This could well be the case in Kingswear.

DISCUSSION

Ivy Cove

Mr Shepperd’s suggested site near Ivy Cove (orange spot in figure 1) best matches the location shown in Bowen’s map (figure 3). There is no sign of a previous building there but this is not unexpected after this elapsed time. It is possible that a tower could have existed there but there is no space for any accompanying meeting room. If it had been a place of worship then there is a question of where the congregation might have come from as there are no recorded dwellings nearby. A tower here might have served as a navigation aid but a better site for this would be on the skyline as in figure 4.

Coleton Fishacre

Watkin16 wrote that a medieval chapel is recorded at Coleton and is thought to have been built by the “de Fishacre” family and is unlikely that it was anywhere near the 1930s house of Coleton Fishacre which was built on a new site as far as is known. However the National Trust has indicated it as a possibility – purple spot on figure 1.

Downend

The suggestion for this site (red spot in figure 1) seems to have originated from an article written by Russell and Yorke17 in 1953:

The famous coastal map of Henry VIII [figure 5] shows the chapel in ruins, and Saxton’s map of the county in 1575 [figure 2] marks Trinity Chapel, although his scale allows him little space for such minor landmarks.

Trinity Chapel, however, was almost certainly a thousand yards northward [of the present Daymark] where Down End dominates the coast for many a mile. From Colaton Farm a lane slopes eastward up to the highest point of the down at 525 feet above sea level, and the fields on the north of it are shown on the Tithe Maps as Chapel Park. Here indeed was the natural site for a chapel, set up as a landmark for mariners and perhaps as a beacon site in time of storms. If Trinity Chapel stood at Chapel Park it may well have been manned by the priest at Coleton, where there was a chapel set up by the Fishacre family. No trace of the building has been found, so far as the writer is aware.

Russell and Yorke18 also reported that the walls of the chapel were pulled down about 80 years ago. They wrote in 1953 so this would be about 1873.

Russell and Yorke note that Leland19 visited the chapel at Downe in about 1540, figure 10, although Leland does not mention Coleton Farm as being nearby. Down and Downend describe a general area of the end of the peninsular and the name could be used for any of the sites mentioned.

“I ferid over from Dartmouth Toun to Kinges Were, a praty Fisschar Towne against Dertmouth, wherof Sir George Carew is Lorde. This toun standeth as Pointlet into the Haven. These Thinges I markid on the Est side of the Mouth of Dermouth Haven: First, a great Hilly Point caullid Doune, and a Chapelle on it, half a Mile farther into the Se then the West Poynt of the Haven; Bytwixt Downesend and a Pointelet caullid Wereford is a litle Bay; Were is not a Mile from Downesend inner into the Haven Kingeswere Toun standith out as another Pointelet, and bytwixt it and Wereford is a praty little Bay; a litle above Kinges Were Town goith a title Crek up into the Land from the Maine Streame of the Haven, caullid Water Hed, a Place meete to make Shippes yn.”

English Heritage20, state that “the site was once an admiralty flag station in 1800 but that there is no surface evidence in the indicated area for any of the features associated with this site. However a pronounced kink in the hedge and a broad area of verge to the west of the track to Brownstone may be associated with the site. It is a local high point (spot height 532 feet) and lies at SX 904435100. During the last world war it was the site of a radar station.”

The site was obviously a good place for an admiralty signal station and a wartime radar station and probably is a good place for a landmark or beacon for mariners but was there a pressing need for a navigation aid in 1258 when there is a recorded reference to a chapel at Coleton? In both the tithe map of 1838 and the Fownes-Luttrell sales map of 1874 the site is shown as part of another field. Surely if this had been the site of a chapel it would have been either on a separate plot and fenced off or linked to Upper Chapel Field to the west, especially as the chapel was said to be still in existence at the time the tithe maps were drawn.

Coleton

The main house at Coleton Farm was once the building to the north of the site of the chapel, figure 6. In 1938 the old farm house was severely damaged when a large beach tree fell on it in a gale. Mrs Marjorie Reeve was living at the farm at the time and the tree crashed through her bedroom – luckily she was at Sunday School when it happened. She had been told that one of the rooms in the house, at the top of a flight of stairs, was used as a penance room when the house was a monastery – coloured green in figure 6. It had a small opening, about 1 ft. by 1½ ft. at chest height, with two wooden doors which opened onto the back landing. The owner, Mr D’Oily Carte, decided that the old house was not worth repairing and so built the Reeve family a new one, Coleton Barton Farm, on another site nearby into which they moved in December 1939.

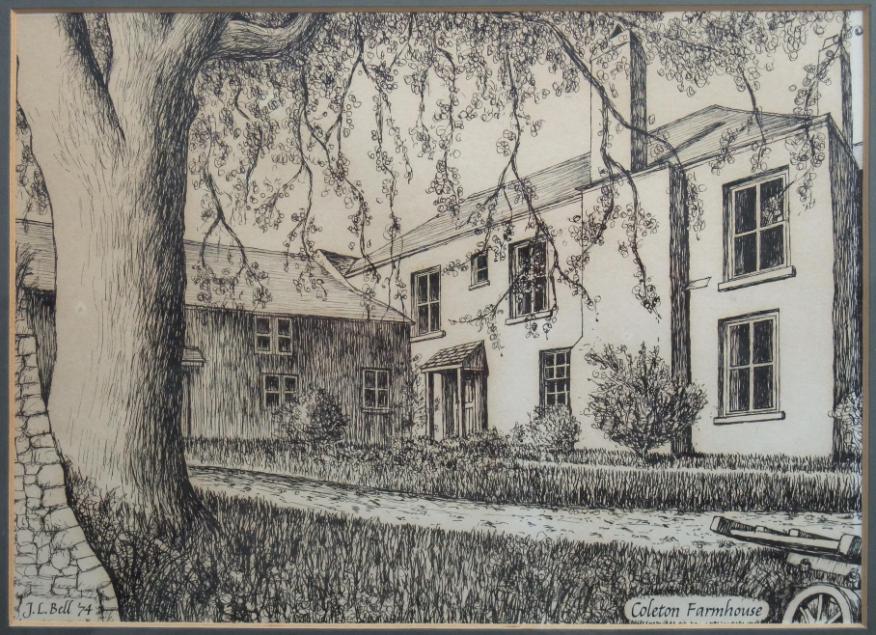

Figure 10 Coleton Farmhouse

Figure 10 shows the old Coleton Farmhouse as sketched in 1974. The building was badly damaged at this time and the artist would have interpreted how it had looked in better days. Mr Sheppard knew the old farm house when he was head gardener at the estate from 1953. The old building had very thick walls, with slits as windows. He also recalls there being a curved staircase up to a small room which he knew as a priest’s prayer room.

Figure 11 South wing of the original Coleton Farm

Figure 12 Remains of a wall (left) opposite the south wing

The site of the old house has been cleared but the south wing of the house, variously described as the servant’s quarters or a barn, remains figure 11. Opposite the wing, on the other side of the lane is an old wall exactly where the presumed site of Trinity Chapel should be, figure 12.

Figure 13 Remains of a south facing wall

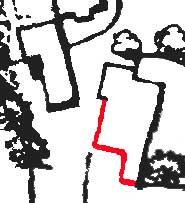

Figure 14 Remaining part of the wall of the chapel shown in red

Figure 13 is a view of the south side of the wall with an opening or doorway in it. Figure 14 is an enlargement of the 1864 OS map with that part of the wall still remaining shown in red.

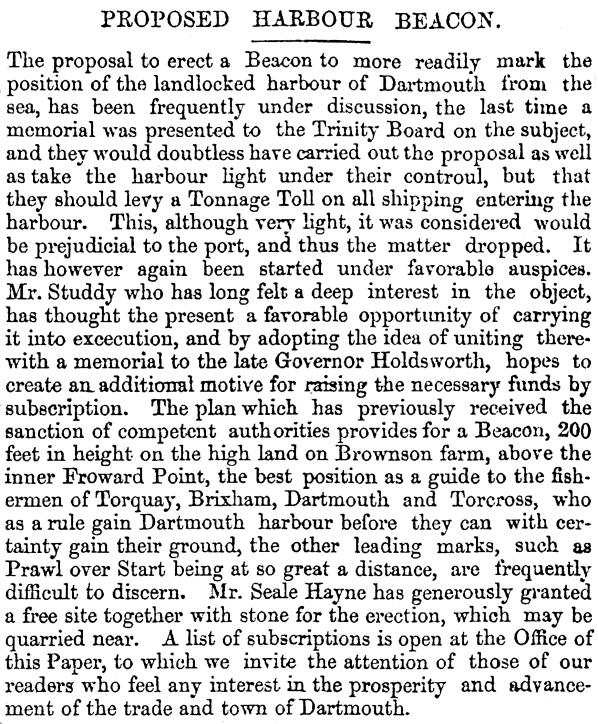

Day Mark

Trinity Chapel was clearly used as a landmark for shipping and presumably at some time it fell into disrepair and was no longer sufficiently visible from the sea. A letter to the Dartmouth Chronicle in June 1855 proposed the erection of a tower to mark the entrance to the river Dart in memory of the late Sir Robert Newman who had died in the Crimean war. In February 1861 a firm proposal was tabled, figure 15, this time to be as a memorial to Governor Holdsworth. Land for the beacon, half a mile south of the site of Trinity Chapel, was given by Seale Hayne and a fund was established to pay for it. However there is no discovered record of the beacon being specifically to replace the tower of Trinity Chapel.

CONCLUSION

The strongest evidence for the site of Trinity Chapel are the maps of 1575 and 1754 which show the chapel as a landmark at or near Coleton together with sketch of the landmark in the pilot of 1693. The sketch correlates well with the plan of a building still shown at the site in the Ordnance Survey map of 1864. A chapel at Coleton was granted a chantry in 1258 with one of its feast days that of the Holy Trinity. No other site has such clear provenance. The chapel is said to have been demolished in the 1870s although some parts of its walls remain. What is not so clear is when Trinity Chapel was built and whether it was the first chapel in the Kingswear area preceding that of St Thomas of Canterbury. Figure 13

Dartmouth Chronicle, February 1861

The font in Kingswear church is fourteenth century in design and has clearly been left outside for many years where it suffered from the weather. During the puritan Commonwealth period fonts were banned from churches and were either destroyed or used for other purposes elsewhere. There is no evidence that the font now at Kingswear was not always associated with Kingswear but clearly it has been outside for a considerable time. If it was imported from another religious establishment then it may have been from Nethway or Boohay. Possibly it even came from Trinity Chapel at Coleton except that another font exists as being from there. The owner of the coat of arms on the font could be of importance in establishing the origin of the font, but is as yet untraced.

At some time the tower of Trinity Chapel must have collapsed thereby denying the shipping and fishing community of a valuable beacon marking the hidden entrance to the river Dart. The loss the tower could have given rise to a demand for a replacement which resulted in the present Day Mark but as yet no direct connection has been found.

1 Watkin, Hugh R. The history of Totnes Priory & medieval town, Devonshire; together with the sister priory of Tywardreath, Cornwall, p96

2 Ellis, Arthur. A History of Brixham and its People. p27 (1951), Brixham Museum & History Society (1992)

3 Watkin, Hugh R. ibid, p804

4 Watkin, Hugh R. ibid. P155

5 A chantry was a chapel or altar which also had an endowment to pay for masses and prayers for the soul of the endower who was often later also buried there. Detailed explanations can be found in

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chantry and http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03573c.htm

6 Cook, G H, Mediaeval Chantries and Chantry Chapels, (1947), Phoenix House Limited, p xi

7 National Trust Report: NT Archaeological Survey, Dart Estuary, East Devon. Caroline Thackray. (1984).

8 Ellis, Arthur. ibid, p 45. Brixham Museum

9 Polwhele, Richard. The History of Devonshire, (1797-1806). Reference not found on first attempt

10 Ellis, Arthur. ibid. p 56

11 Private conversation, July 2009

12 Cresswell, Beatrix. Notes on Devon Churches. The fabrics and Features of interest in the churches of the Deanery of Ipplepen, pp159-161.(1921)

13 Reference needed

14 Tyrrell-Green, E. Baptismal Fonts, SPCK (1928)

15 Bond, Francis, Fonts and Font Covers, Henry Frowde (1908), p207

16 Watkin, Hugh R. Proceedings at the 71st annual meeting, 1932, Transactions of the Devonshire Association, (1932). Not p42?

17 Russell, Percy and Yorke, Gladys. Kingswear and Neighbourhood. Transactions of the Devonshire Association, 85 (1953), p73-4. The full article, with extra material, is reprinted as a separate booklet by the Kingswear Historians. (2008).

18 Russell, Percy and Yorke, Gladys. ibid. p77

19 Leland, John. The Itinerary of John Leland the Antiquary, p53. Published by Thomas Hearne. Oxford (1711). Another version of this document has the extract on page 33. It also appears in Lelands Itinerary 1 pt 3 1535- 43 223 (Ed L T Smith 1964)

20 Wilson-North W R. RCHME Field Investigation, (1991), English Heritage

Kingswear

November 2009